On a September afternoon in 1980, I boarded the Coromandel Express at Howrah station. The train arrived at Chennai Central (then ‘Madras Central’) early evening the next day. I caught another train from Egmore that night, and disembarked at my destination, Cuddalore, the next morning. I remember very little about the details of that 45-hour trip because I was caught in the grip of an infatuation that continues, intermittently, to this day.

Before I boarded the Coromandel, a family friend who had returned from the U.S., gifted me a Rubik’s Cube, the classic 3×3 version. The Cube wasn’t yet commonly available in India and I had never seen one before. I would learn later that it had already been around for six years. The inventor, Ernő Rubik, an architecture professor from Hungary (then a Communist country part of the Soviet Bloc), was already world-famous.

I spent that entire journey sleeplessly playing with it. Slowly, I worked out a solution: first solve a layer, then solve the corner cubes opposite that layer, then solve the edge cubes. I could easily reduce to just two edge cubes out of place. But fixing that last pair was very, very hard. Working it out took most of the 45 hours and my solution was a long way from optimal.

Within months, the Cube became commonplace. Local knockoffs were being sold for ₹10-₹20. Many people had worked out solutions, or mugged them up from “cheat-sheets”. Chess players were using chess clocks to compete in speed cubing contests. “Speedcubers” were taking them apart, and lubricating the mechanisms with Vaseline to make them turn faster.

Today, 50 years after Rubik invented this puzzle that was so intriguing it took him a month to solve, it continues to be popular. This despite being a mechanical construct in a digital age. Officially, over 500 million Rubik’s branded cubes have been sold, and Canada’s Spin Master Corp., which owns the brand, claims it made around $75 million in revenues from it in 2023. Unofficially, knock offs to the tune of several billion have been sold.

“I think probably the Cube reminds us we have hands… You are not just thinking, you are doing something. It’s a piece of art you are emotionally involved with… New generations have developed the same strong relationship with the Cube”Ernő RubikInventor of the Rubik’s Cube

Journey of evolution

Ambar Chatterjee, who retired as the head of the nuclear physics division at Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, is someone else with cubing experiences from 1980. He bought a cube off a Mumbai footpath and quickly realised he would have to write down his moves to devise a systematic solution.

Chatterjee (also a keen chess player who is president of the All India Web Chess Federation) borrowed an idea from chess to figure out a notation that was similar to what is now the standard cube notation. He took the cube apart to understand its mechanics and spent about a month to record all the transforms he worked out.

But when he showed the solutions to his BARC colleagues, they were unimpressed. “I had to keep looking at my transformation sheet and my notes, while newspapers were already full of stories of youngsters who could solve it in a few minutes,” recalls Chatterjee. He fine-tuned his methods and practised solving without his notes. “I came across an article by mathematicians from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Science Today. One of them solved the cube using group theory. The sequences given were much shorter than the ones I had worked out,” he remembers.

Milestones

After its invention in 1974, the puzzle was called Magic Cube and renamed ‘Rubik’s Cube’ in 1980

The first-ever Rubik’s Cube World Championship was held in Budapest in 1982. The winning time that year was 22.95 seconds

In 1987, when it was launched internationally, Rubik’s Cube sold more than 14 million units worldwide

The Cube made its pop culture debut with an appearance on ‘The Simpsons’�in 1991

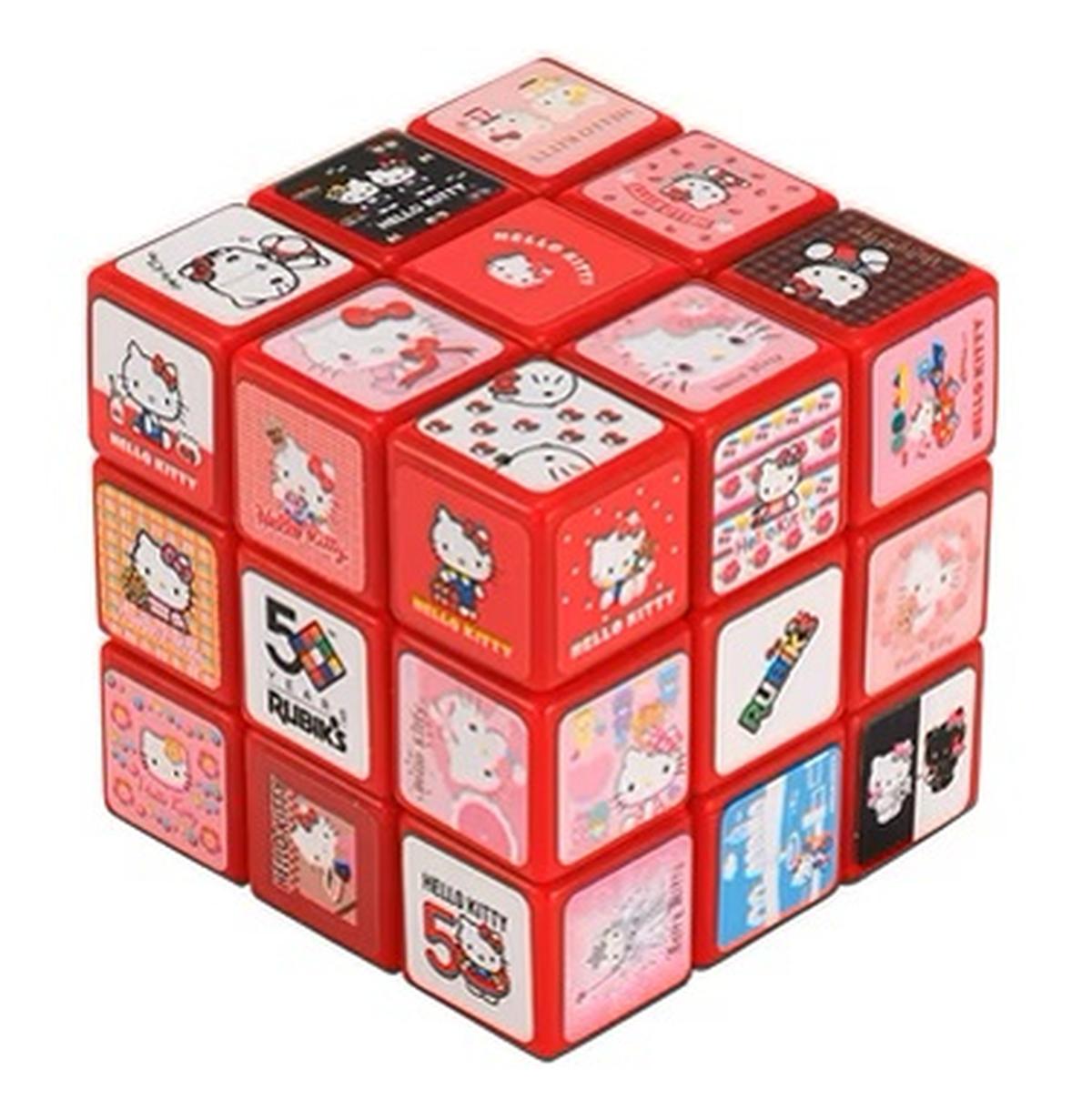

As part of 50th anniversary celebrations this year, limited edition Cubes with Batman, Black Panther, Wednesday Addams, Barbie and Hello Kitty themes have been announced

Now, at 71, Chatterjee says, “I want to try it again afresh! This time, I am going to replace the stickers with chess figurines. The six faces would be king, queen, rook, bishop, knight and pawn. This may introduce another constraint of symmetry since the pieces will need to be oriented with the same side up.”

Cubing remains a global passion with old-timers like Chatterjee looking to innovate while many youngsters pick up the mantle of quick-solving. India has plenty of hobby cubers and many local speed-cubing competitions, though it’s yet to make a big splash at the world speed-cubing level. It does have cubers who have done unusual things such as solving it with their feet, though. Speed cubes are no longer lubricated by Vaseline — they come with internal magnets and better materials to twist smoother.

There are also multiple variations on the original Cube. The World Cube Association (WCA) hosts biennial “twisty” world championships with 17 variants, including cubes with different numbers of pieces to each side (2×2, 3×3, all the way to 7×7), as well as modified shapes such as the Pyraminx (pyramid) and Megaminx (dodecahedron), blindfold events, and so on. The WCA also helps enthusiasts organise cubing competitions everywhere.

Fastest fingers

Speedcubing champions Max Park (left) and Feliks Zemdegs.

There are speedcubing legends like Max Park, the Korean-American world champion. Ratified WCA world records are measured down to the hundredths of seconds. Park’s speed record for the 3×3, which he set in 2023, is 3.13 seconds. Park, who is autistic, has a legendary rivalry with the Australian champion, Feliks Zemdegs, though they are also close friends. There is a moving Netflix documentary, The Speed Cubers, featuring these two champions and their relationship. The 100 fastest single-solve WCA times are all under 5 seconds and there isn’t an Indian in that list. The national championships have, however, featured sub-5-second timings but no Indian has yet done it in a WCA event.

The learning curve for solvers has changed as the world has gone digital. Over the decades, hundreds of solving algorithms have been developed and videos galore are available on YouTube. As mentioned earlier, solutions tend to come from mathematicians who understand Group Theory (the relevant branch of maths) and from youngsters with a talent for pattern recognition.

Special edition Rubik’s Cubes

There’s been concerted efforts to find ‘God’s Number’. This is the minimum number of twists required to solve any of the 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 (43 quintillion) configurations of a 3×3 cube. In 2010, God’s Number was proved to be never more than 20 twists of 90 degrees or more, by a group that used computer time donated by Google.

There are many Indian coaches who teach solving algorithms. Vani Muthukrishnan, a 45-year-old based in Negercoil, is one of them. The former schoolteacher started cubing 13 years ago and eventually became a full-time cube tutor as well as organsier of cubing competitions on behalf of the WCA. She’s also an enthusiastic competitive solver herself and has attended 13 official WCA competitions. “I happened to download written notes from the Internet and it took me a week to do my first solve,” Muthukrishnan says, adding, “That was amazing and it gave me a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. Then a friend asked me to teach her daughter.”

After the pandemic, all her classes are online and while she deals with small batches of two-five students and charges between ₹200 and ₹500 per hour, there are enough takers for her to do this as a profession. Her students come from all over the world and there’s a wide age dispersion, too. “My very first student was a doctor and his daughter. Now that girl has become a doctor, too. Some of my students joined because they were impressed seeing their children or grandchildren solve the Cube.” Muthukrishnan also conducts free workshops, including free training for orphanages.

School children take part in a Rubik’s Cube challenge in Mangaluru.

| Photo Credit:

Manjunath H.S.

A therapeutic tool

As research around the Cube indicates, software developers tend to be interested in cubing and the hobby runs across generations. Sirish Somanchi, now in his mid-40s, first started playing with the Cube 30 years ago. His children also like solving.

Somanchi points out how the Cube shows up in pop culture. “For example, Will Smith gets a job in the 2006 movie The Pursuit of Happyness because he can solve the Cube.” There are also anecdotes of the Cube featuring in Google and Microsoft interviews. However, Somanchi chuckles as he admits he’s never been asked to solve a cube at a professional interview. The Hyderabad engineer also says his children have learnt by watching YouTube videos, whereas he picked it up by searching online for algorithms.

In the case of S. Aswin, another software developer, the interest was inherited. The 24-year-old Chennai resident was fortunate in that his father, also an architect like Rubik, was fascinated by the Cube. So he grew up with it and variants such as the Snake and the Megaminx at home. Aswin loves creating interesting patterns and playing with the variants as well as simply solving.

Shaun Pinto from Bengaluru is a classic representative of the younger generation of cubers. The 15-year-old has just finished Class X and he averages under 15 seconds solving the 3×3. “I first solved it when I was seven and could do it then in about five minutes, and then slowly started chipping away at my times. I used to compete quite a bit a few years ago,” says Pinto. “The cubing fraternity is one of the most wholesome and welcoming communities, it’s easy for anybody to feel welcome, no matter their speed, age, disabilities, etc. Children who get into speedcubing have really good social circles, a healthy sense of community and belonging, and end up with valuable life lessons. The pursuit of improving at it is also a very beautiful one.”

His words are a reminder of Park’s experience. Park’s mother Miki taught him the Cube in order to help him develop his motor coordination skills. She discovered him starting to connect with other cubers and become more socially comfortable as well. Using the Cube as a therapeutic tool, or a way to enter an accepting community may be a possibility.

Professor Rubik conceptualised the Cube as an interesting teaching device that would help students develop a sense of 3D shapes and patterns. It also helps to develop visual memory and hand-eye coordination as solvers learn more algorithms and instantly identify what works. Fifty years down the line, the little multicoloured toy has become a cross-cultural icon that helps connect people across continents.

The writer is a journalist with an abiding interest in mathematical puzzles.