[ad_1]

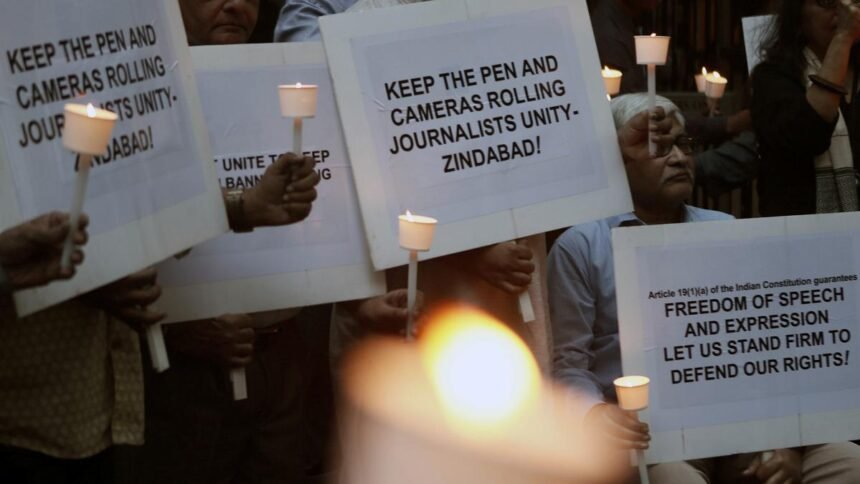

Many institutional news media have lost credibility due to which they are unable to establish a baseline of facts or exercise narrative control. Picture shows journalists during a candlelight vigil in Mumbai against police brutalities and attacks on press freedom.

| Photo Credit: Reuters

The democratic political process in India is broken. It is not just that the institutional machinery has been captured, but that it is becoming impossible to alter the balance of power on any issue to chart a new way forward. At its heart, the democratic political process is not about regime change or “resistance”. The purpose of democratic politics is to facilitate constructive collaboration, of which capturing power and regime change is one part. Seen thus, democratic politics is about building consensus in favour of certain paths and providing platforms for collective action. But all traditional sites of consensus-building — public discourse, civil society, and political parties — have evolved to structurally impede dialectical cooperation.

This is different from the issue of institutional capture because institutions of the state are downstream of the political process. Such institutions can neither be in the business of facilitating collectives nor mooting alternatives; they instead derive their credibility from procedural integrity. What is at stake here is more fundamental to our polity and speaks to our inability to collaborate. Consequently, even on issues which have deep public resonance, we as a polity are unable to move beyond outrage, protest, or resignation. It is crucial to identify the pathologies affecting each of these sites if we are to restore the democratic potential of our political process.

The nature of discourse

In a democracy, public discourse provides the space for the back and forth necessary to evolve consensus. However, three connected developments have rendered our public discourse unable to facilitate this. First, many institutional news media have lost credibility due to which they are unable to establish a baseline of facts or exercise narrative control. Second, the rise of social media has decentralised the manufacture and propagation of content making virality instead of substance the primary determinant of value. As a result, engagement is prioritised over quality or veracity. Third, with the loss of credibility of many mainstream media, there has also been a rise in hyper-partisanship wherein people are no longer interested in dialogue or deliberation and news/content is primarily a tool to promote factional interests. Finally, the proliferation of media has led to the fragmentation of our collective attention while the steady stream of “content” has made all issues transient. In this backdrop, gaining visibility and capturing attention is more important than dialogue. Consequently, the public discourse has become a site for a million individual battles to capture attention and reinforce tribal affiliation.

Civil society plays a crucial role as the voice of conscience in any polity and is the natural site to moot alternatives. However, the locus of liberal civil society action has increasingly moved towards the state and its institutional intermediaries; civil society has become dependent on a permissive state to be able to function. In this model, civil society derives legitimacy from normative purity instead of drawing strength from its representativeness. It is thus suited more to single-issue campaigns than its ability to reconcile multiple viewpoints through negotiation. Civil society groups are also marked by the proclivity to bypass the political process in favour of institutional processes, such as judicial or bureaucratic interventions, to advance their agenda.

Finally, political parties have their own pathologies which shift focus to internal issues and reduce space for deliberation. Conceptually, one aspect of the role of the elected representative is to extrapolate constituency issues into a policy agenda. However, the average elected representative does not have the power and often even the inclination to do so, within the party setup. There is also uncertain electoral pay off from influencing the policy agenda versus directly intervening on behalf of the constituents for delivery of various services. Moreover, elections, even at the constituency level, involve a complex and variable mix of “representation” of constituency, State, and national issues. Consequently, all candidates except the local strongman derive a decisive fraction of votes from the party symbol. This tilts the balance of power heavily towards decision-makers for party tickets within the party. This is further compounded by the fact that institutional positions of power in any party are a fraction of the actual aspirants leading to a preoccupation with internal machinations and sycophancy.

Our ability to come together

These various pathologies feed off each other to fracture our ability to come together. The media may highlight issues but moving forward requires organisation by civil society and political parties. On the other hand, the dysfunction in our information ecosystem has powered the rise of unserious individuals to positions of influence. The top-down nature of parties has altered the structure of civil society by raising the bar for grassroots mobilisation to an untenable height, leading civil society groups to direct their energies into lobbying through intermediary institutions or becoming agents for the execution of bureaucratic projects. This has depleted the organisational strength of civil society and reduced its ability to intervene in the political process for correctives. The dialectical nature of these pathologies resists easy fixes but for the world’s largest democracy, the complexity of the issue is not reason enough to not try.

Ruchi Gupta is Executive Director of the Future of India Foundation. X: @guptar

[ad_2]

Source link