[ad_1]

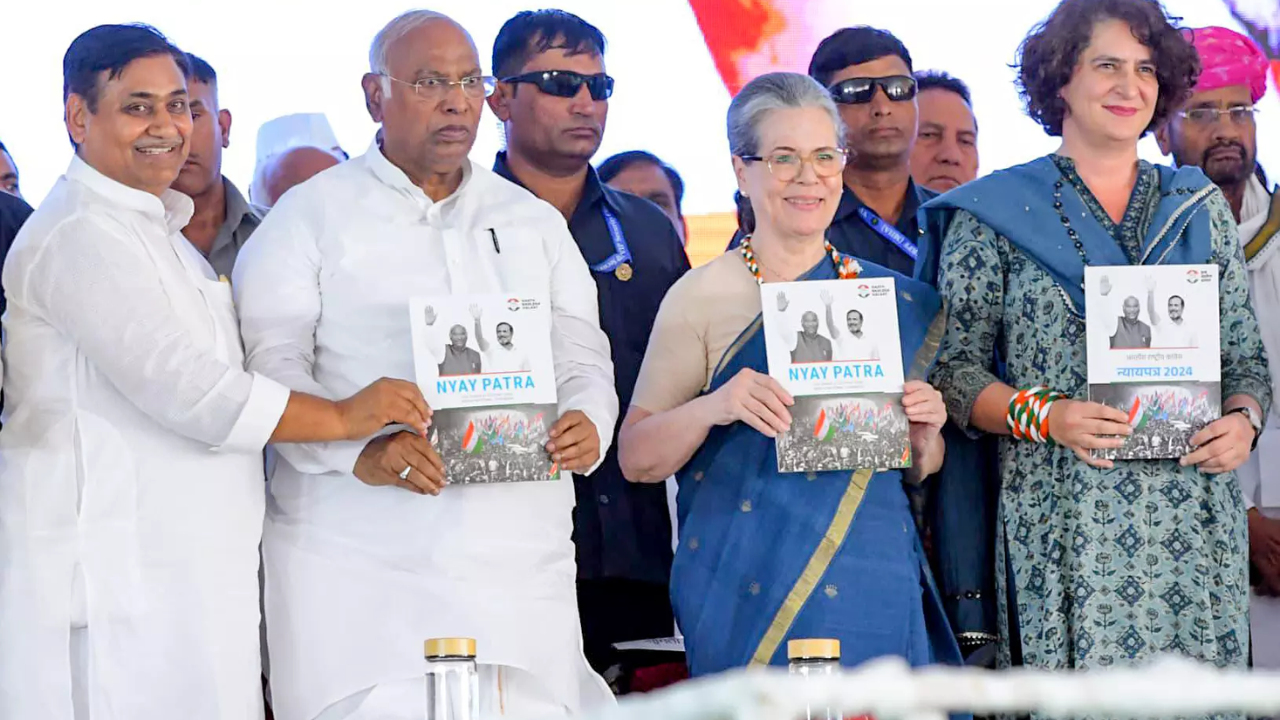

NEW DELHI: The Congress Manifesto 2024 is heavy on reservations in the private sector, with the party seeking to fulfil two key promises – job quota in private sector and education quota in private institutions – that it could not deliver during the decade of UPA in office.

The pledge to create a “diversity commission” to “measure, monitor and promote” diversity in public and private employment and education, has shades of what Congress had promised in 2004.The manifesto then had promised to create a “national consensus” on reasonable SC/ST share in private sector jobs, and had proposed to hold a dialogue with the industry to devise ways of accomplishing it.

A group of ministers held talks with the industry, raising the tempo to the point of the possibility of a law to enforce quotas in the private sector. Later, amid uproar from the corporates, the govt settled for “voluntary” affirmative action, with a high-powered committee in the PMO to follow up on the issue. The compromise offered never raised hopes of any forward movement.

Though the ‘Nyay Patra (doctrine of justice)’ has again promised a voluntary measure for the private sector, the “diversity commission” is a crucial step forward as it would collect caste-wise employee data, including of OBCs, from individual companies. It is likely to be used to create social and institutional pressure on corporates about any low share of weaker sections on their rolls.

Given that Congress has already made “caste survey” a flagship plank, the diversity commission seems like a follow up body. But compared to private jobs, it is in diversity in private education that Congress seems decisive.

The frontal promise “to enact a law to provide for reservation in private educational institutions for SC/ST/OBC” is a direct reference to what the Congress-led UPA did under then HRD minister Arjun Singh in 2008.

While the govt had effected the 93rd constitutional amendment to enable quotas for OBCs as well as SC/STs in public and private institutions, the enabling Act limited it to introducing OBC reservation in the govt’s higher education institutions.

The reason for limited action on the original idea to extend the quota frontiers was the backlash from within Congress as well as from outside.

The introduction of 27% OBC quota in IITs and IIMs, besides central universities, led to an uproar, with claims of limited infrastructure and compromise on quality, forcing Congress on a prolonged fire-fighting mode.

The fresh vow to take the incomplete UPA task to its logical conclusion is a novel social justice move in view of the proliferation of the private sector in education to make up for the shortfall in the intake capacity.

The pledge to create a “diversity commission” to “measure, monitor and promote” diversity in public and private employment and education, has shades of what Congress had promised in 2004.The manifesto then had promised to create a “national consensus” on reasonable SC/ST share in private sector jobs, and had proposed to hold a dialogue with the industry to devise ways of accomplishing it.

A group of ministers held talks with the industry, raising the tempo to the point of the possibility of a law to enforce quotas in the private sector. Later, amid uproar from the corporates, the govt settled for “voluntary” affirmative action, with a high-powered committee in the PMO to follow up on the issue. The compromise offered never raised hopes of any forward movement.

Though the ‘Nyay Patra (doctrine of justice)’ has again promised a voluntary measure for the private sector, the “diversity commission” is a crucial step forward as it would collect caste-wise employee data, including of OBCs, from individual companies. It is likely to be used to create social and institutional pressure on corporates about any low share of weaker sections on their rolls.

Given that Congress has already made “caste survey” a flagship plank, the diversity commission seems like a follow up body. But compared to private jobs, it is in diversity in private education that Congress seems decisive.

The frontal promise “to enact a law to provide for reservation in private educational institutions for SC/ST/OBC” is a direct reference to what the Congress-led UPA did under then HRD minister Arjun Singh in 2008.

While the govt had effected the 93rd constitutional amendment to enable quotas for OBCs as well as SC/STs in public and private institutions, the enabling Act limited it to introducing OBC reservation in the govt’s higher education institutions.

The reason for limited action on the original idea to extend the quota frontiers was the backlash from within Congress as well as from outside.

The introduction of 27% OBC quota in IITs and IIMs, besides central universities, led to an uproar, with claims of limited infrastructure and compromise on quality, forcing Congress on a prolonged fire-fighting mode.

The fresh vow to take the incomplete UPA task to its logical conclusion is a novel social justice move in view of the proliferation of the private sector in education to make up for the shortfall in the intake capacity.

[ad_2]

Source link